What is matter, and how can we think of matter? ‘Matter’ is not something real in the sense that it can be given in our experience. It is not something that we can feel, touch or see as we see this apple tree or this cat.

Matter is an ‘abstraction,’ as they say, or an imagined entity supposed to exist in all material things, in the same way in which the character of being a mammal or an animal exists in all concrete and material cats or dogs. As with matter, we cannot see or touch ‘mammality’ or ‘animality.’

The latter are only abstractions of our minds that we discover while building increasingly larger classes of living beings and climb thus from the individual concrete cat to the larger class of mammals, then to the larger class of terrestrial animals, to reach finally the largest class of animals (living both on ground and in water).

As a similar abstraction, matter is the most widely spread feature we find in all material things, whether they are lifeless or alive. This cat or an animal, in general, are as material as a rock, an ocean, or a light wave.

But what are the features or properties that we can find in each material being? The first two necessary features are spatiality and temporality: whatever is material is both spatial and temporal. However, since temporality is a necessary feature of matter, we should not be able to think of it as resting in a quiescent condition, in passive repose.

Imagining some abstract piece of matter as lying inertly and changelessly in space and time is a logical error that we usually commit because we do not think profoundly enough about what time means.

We start from our usual experience, in which we see things lying around us without being affected by time. Of course, this is due to the shortness of the period that we take into account. If we considered a much longer time, we would notice changes even within the most change-defying things, like a diamond.

Once you add time into the equation of Being, you introduce motion, or more generally, change. Motion is a more concrete form of change in which only the change in spatial position is considered. Whenever we think of something as going from moment A to moment B, we must think of it as necessarily changing, either spatially or in other respects. We just overlook this aspect.

This is due to the fact that we cannot gain the representation of time if we do not go from one place to another, from one position in space to another. And, if we assumed that everything in space was identical, that the whole of space was an infinite void, either we or that objective empty space could never rise to the reality of time.

Time necessarily implies spaces that are and look different. Only as passing through such different spaces can time emerge as a new reality, different from space.

Coming back to matter, if the infinity of space had been filled up with an absolutely identical and passive matter, time could never have occurred. But neither could the universe as we know it today, as a cosmos of a myriad coexisting differences and oppositions.

We saw that real matter cannot be met in reality, in the same way that we do not here meet any animality, that matter like animality is an abstraction. Matter is certainly a thought possibility, which, used with respect to everything that exists, logically implies eternal endurance.

The whole universe is matter, and the matter of the universe will persist as long as the latter endures. This is what the well-known principle of knowledge says: nothing is lost or disappears in nature, but everything is changing. As a thought possibility or thought entity, then, matter must be something that defies time.

Matter is not simply that which corresponds inside of time to the flow of time – that which supports the identity of time over the latter’s continuous transformation of one moment into another moment – that substantia which lies at the bottom of all phenomena under all of their abundance of different qualities.

It is something that actively opposes time; that, in our logical thought, negates time. Matter is then a form of resistance to the flow of time, actually the first form of resistance when we think logically about the whole of reality.

Whatever exists as real must be thought of as resisting: either as resisting (for a while) the influence of time or as resisting something external to itself that tends to occupy its spatial position. Resistance in space is a logical consequence of resistance in time since time is necessarily interconnected with space, as we saw.

Resistance has a negative connotation in that it expresses the fact that an entity ‘negates’ another factor when the latter tends to subordinate or rule over it: it repels it. Therefore, wherever we meet matter, we also meet repulsion, i.e., the tendency of matter to repel another piece of matter.

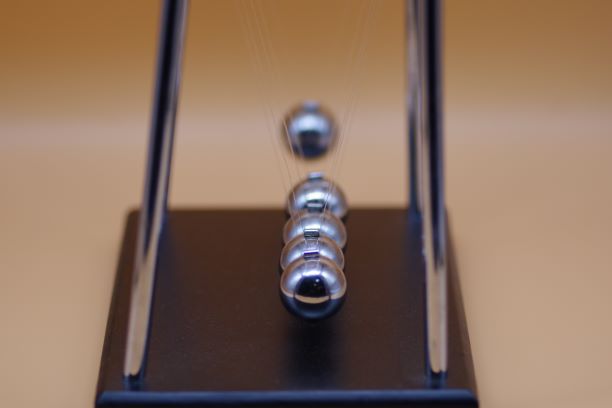

Repulsion can happen even at a distance. The most visible form of repulsion is that between magnetic poles of the same type. But repulsion is thought of as being present in many other processes and phenomena. For example, when one ball hits another ball, the latter ‘reacts’ by rejecting the first ball. It is not simply resisting the impact of that ball: rather it rejects it; it is throwing it away; it repels it.

The fact that matter is a spatial entity constrains us to think of it as being also endowed with attraction: because a piece of matter occupies a place, its components do not simply repel each other but also attract each other.

If the matter was endowed only with repulsion, no material body – i.e., no unity between material components – could ever be possible. To overcome repulsion, which we derived earlier, you must posit attraction.

Undoubtedly, all these qualities or properties of matter were acknowledged long before Hegel. They were assumed based on the generalization of our experience with material bodies. For example, the impenetrability of matter (which is the quality of repulsion) is what we see when we push a tree: our hand does not enter the tree’s trunk as happens when we put our hands into water.

Hegel’s aim was not simply to present and describe them as generalizations of our experience but to show what other thoughts made them possible. In this sense, his method is akin to the Kantian ‘construction’ of concepts, which Hegel also mentions concerning the ‘construction of matter’ accomplished by the author of the Critique of Pure Reason in his Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science (Hegel 1970, p. 241).

Reference:

Hegel’s Philosophy of Nature, edited and translated by M. J. Petry, vol. I, London, George Allen, 1970.